A WORKING MAN’S AFRICAN DOUBLE

Chapter 2:

Russ Gould

In this series of

articles, the author explores the concept and actual performance of an

affordable double rifle of sufficient power to handle large African game. This,

the second article in the series, describes the use of a Valmet

375/444 double rifle

on small- and medium-bodied plains game

on Safari in

|

|

|

Author’s Valmet 375/444 and Kit Ready for Proving in |

Thick green Acacia bush and at-times chest high yellow-gold grass attest to the good rainfall received in the summer and fall of 2004 across much of South Africa, and specifically across the undulating ridges and valleys of Umkanyakude (“Shines From Afar”), a private game farm located 20 kilometers North of the small town of Hluhluwe and not far inland from the warm waters of the Indian Ocean.

Dr Mark Sutherland, owner of the farm, takes pride in the trophy-class Nyala and rare Red Duiker that occur in good numbers on the property, now that the former cattle ranch has been returned to its natural state. Each year, approximately 60 of the 250 to 300 Nyala on the property are either taken as trophies or darted for relocation.

In addition to these signature species, indigenous Kudu, Bushbuck, Reedbuck, Impala, Grey Duiker, and Warthog populations have increased under Mark’s scientific management of the property. Mark has also reintroduced Blue Wildebeest, Zebra, Giraffe, and Waterbuck, although the latter have had difficulty dealing with bush ticks that abound in the area. Natural predator populations including the rare spotted hyena, caracal, and leopard have also increased in line with that of their prey.

Proximity to the ocean and fertile soils support ample

vegetation and high concentrations of game. In contrast to the

Mark’s property is one of the few remaining privately-owned farms

in this subtropical corner of

|

|

|

Accommodation

was provided in comfortable tents erected on wooden platforms. |

I quickly made myself at home at Mark’s camp, an attractive

cluster of tents set on wooden platforms among a grove of trees overlooking a (now

dry) river bed. An outdoor kitchen under thatch, equipped with potable water

and gas appliances, opened onto a small deck overlooking the river. Immediately

below the deck, a small waterhole fed from the camp borehole ensured adequate

water for the animals, providing interesting viewing during the

|

|

|

|

Open Air Kitchen

and Deck Overlooking the |

View From the Deck

of Riverbed and Water Hole |

A reed enclosure served as a shower, fired by a wood boiler. And running water was provided in one of the three tent units and at the flush toilet situated some distance from the tent area. What the camp lacked in modern comforts and conveniences, it more than made up in ambience. To my mind, a bush camp such as this is far more enjoyable than the lodge accommodation now the norm on ranch-style hunts, as it provides a real African flavor to the experience.

|

|

|

375/444

Cartridge, Based on the 444 Marlin Case, is Now a Factory Offering from |

The purpose of my hunt was to explore the capabilities and

limits of a Valmet 412 double rifle custom-chambered

for the 375/444 cartridge (444 Marlin case necked to 375), loaded with Speer

235 grain softs over 53 grains of W748 powder. The Valmet supports interchangeable barrels in rifle, shotgun,

and combination calibers, and is relatively trim and light for a double rifle.

Rifle barrels are available in various calibers, the heaviest being the excellent

9.3x74R. This particular example was readily rechambered

from its original 375

As with all Safaris, the hunt began at the rifle range. A sturdy concrete bench under thatch provided a steady rest. After firing a single round from the lower barrel at the designated firing range into the bullseye at around 60 yards, an appropriate range for the conditions, I was deemed ready to hunt.

As with most hunters visiting Umkanyakude, my top priority was the shy and beautiful Nyala, a medium-sized antelope related to the kudu and sharing that animal’s full length mane, vertical body stripes, and chevron between the eyes. While not as impressive as the Kudu’s double spiral, the Nyala’s horns are graceful and its surprising bright yellow legs make it by far the most distinctive of all African antelope. (A 28” Nyala is in the same class as a 55” Kudu.) When alarmed, the Nyala will bark like a large dog, and in flight, it shows a white tail flag very much like the North American Whitetail Deer. The females and immature males are rust red in contrast to the almost charcoal body coloration of a mature male. The animal’s love of thick bush makes it a real challenge to hunt.

|

|

|

Distinctive Yellow Legs and Shaggy Coat Make Nyala

One of the Most Striking African Antelope |

In addition, I wanted to take several smaller species

including the Bushbuck, Reedbuck, Impala and Warthog in order to familiarize

myself with the rifle and its capabilities. The most plentiful species on this

property (and across all of

Impala are extremely challenging to hunt. They are usually found in groups, either

a dominant male with a group of females, or a bachelor herd of younger

males. Their eyesight is very keen as is

their sense of smell. In addition, their stature ensures that their eyes are

positioned just above the tall grass, but below the browse line for optimal

visibility. A hunter, in contrast, has his head up in the foliage, putting him

at a distinct disadvantage to his prey. With practice and considerable stealth,

one can spot a herd though the screen of brush by the give-away tail flicker

without being spotted, about half the time. As soon as the impala catch you in

their “cross fire” of eyes, they will flee, or at a minimum begin snorting and

blowing in a disconcerting way. This is rather humbling and at that point, it

is well nigh impossible to get a shot at any of the group, let alone the single

ram you will be trying to make out. For these reasons, Impala hunting is fun as

well as being inexpensive in comparison to other species.

A note to trophy hunters: record-class Impala are found in

Northern regions of

When a herd is spotted, my normal procedure is to first squat and begin glassing in an attempt to locate the ram. Wind direction is critical. The herd can sometimes be approached by using an intervening bush as cover, but inevitably one or two Impala will be able to spot you no matter how carefully you sneak up on the group. My preferred tactic is to get down on my hands and knees in the grass, and to approach very slowly moving from bush to bush until a suitable vantage point is gained, at which time one must prepare to shoot when the ram is located and is standing clear of his harem.

My first stalk by this method went quite well. Mark, unlike almost any other PH I have hunted with, is happy to let the hunter take the lead, and will drop back during the final approach. This makes you the hunter, not just the shooter. Having spotted a herd late in the afternoon, Mark sat under a shady tree to watch while I crawled, bellied, and duck-walked my way up to a group of Impala unobserved. While crawling, I slung the rifle across my chest freeing up both hands. As if by some sixth sense, however, the Impala kept enough brush between me and them that I could not get a glimpse, let alone a clear shot at the ram. About 10 minutes into the stalk, the group suddenly flitted to my right without warning, possibly disturbed by something else or having caught a snatch of scent in a wind eddy. However, they soon settled down about fifty yards away allowing me to move closer, this time on my belly as the grass was short and I was in an exposed position upslope of the herd. I finally reached a promising firing point behind a small acacia with a fork at just the right height for a kneeling shot. Easing my rifle into the fork, I began glassing through the brush at the ever-moving tan bodies. When I finally spotted the ram sandwiched between two females, I had in turn been spotted by two young Nyala bulls off to the side. They were both staring intently at me. Believe me, these animals have all day to look at you, and they are in no hurry whatsoever to move on. While they have their attention on you, you must freeze or the game is up. Thus check-mated, Mark whistled softly and gestured to call the stalk off. The ram was not very large, so we left the group to look for another.

The dice rolled in the Impala’s favor that afternoon, as we were outspotted by two more groups. We did see a nice male Warthog before he saw us (actually almost ran into us), but he was not fully mature so we let him go on his way, mumbling to himself. As the sun sank into the Western folds of the property, we made our way back to the vehicle and called it a day with about 30 minutes of shooting light remaining.

American hunters, accustomed to shooting at last light, will find that most African PH’s cut the hunt short with an hour or so of light remaining. This is for good reason, as animals wounded at last light are often not recovered until the following day, by which time predators and warm temperatures have often done their work. For these reasons, evening hunts are shorter and shots should only be taken if the hunter is very sure of the shot. Morning hunts are more leisurely and less pressured, not an excuse for sloppy shooting, but there is less pressure on the hunter to make a perfect shot.

|

|

|

African Sun

Rising Over the Distant |

Rising before dawn, we jostled over the two-track roads toward a ridge where a larger ram was known to have established his territory. The sun rose behind a bank of cloud over the distant ocean, filling the sky with a fantastic light show. The air was cool and a little damp, and there was dew on the grass and on the vehicle. En route, we encountered a group of impossibly tall giraffe, who moved off in slow motion as we drove by. We pulled over a few hundred yards from the area we planned to hunt. Cinching my fanny pack around my waist, I slipped two of the short fat 375/444 cartridges into the Valmet, closed the action with a solid click and slung the rifle upside down over my shoulder to keep the barrels from flashing in the sun. Within fifteen minutes of careful walking with the breeze across our front and the sun at our backs, we spotted the group we were looking for slightly below us and about 70 yards away. The grass in this area was knee high, providing enough cover for a hands-and-knees stalk. Moving from bush to bush and tree to tree, not daring to look up, I moved toward them leaving my guide behind to watch the hunt. After what seemed like a long time, I stopped less than 50 yards from the group and began searching for the ram. Some ewes off to my right must have spotted movement, and began snorting. But surprisingly, the group, although alert, did not bound off. To my surprise, the ram appeared less than 40 yards from me, also staring in my direction but with his body quartering toward me with his head to the left. He was a good one. I sat on my right heel with my left elbow over my left knee, rifle pointed toward the impala, and scooched to the side very slowly until I had a clear view of the ram’s chest. The ram was wound up like a coiled spring and the ewes were blowing almost continuously, so I knew I had to make the shot quickly. The scope was set on 4.5x and I put the crosshairs between his breastbone and his left shoulder and squeezed. I wasn’t as steady as I would have liked, but the range was very short and the ram held still. Due to the rather heavy trigger pull, the squeeze seemed to take forever. Just as it broke and the shot crashed, I noted with a sinking feeling that the crosshair had drifted to the left. At that point, the impala were flying through the air in every direction. As best I could tell, the bullet took the ram slightly to the left of the breast bone, which was the wrong side given his stance. At close range, I also realized that I shot a little low using the bottom barrel. I tried to tell myself that the large 375 bullet ought to do its job even if the shot placement was not perfect, and we began searching for the animal. My gut felt light.

My fears were soon realized. There was no blood at all and

the track was hard to follow in the thick vegetation. I would have liked to

call a miss but knew better. Calling for reinforcements in the form of three

trackers, we searched the hillside and the nearby waterhole until

Later that afternoon, one of the trackers told us that he had seen a ram with a group of ewes, limping but not heavily. The rest of the afternoon was spent hunting a herd spotted where the ram was sighted, but the ram we located appeared smaller and had no limp. A day that had started out so well thus ended poorly: a wounded impala somewhere in the thick bush, one of possibly five or so different groups that frequented the same general area.

As I turned the day’s events over and over in my mind, staring into the hot coals of a fragrant campfire, I kept coming back to the question: why no blood?

Early the next morning, with fresh resolve, we resumed the Impala hunt. Parking the short wheelbase Land Cruiser at the same spot, we were soon rewarded by the sight of a loan Impala ram, about fifty yards off, facing directly toward us. Using the guide’s shoulder, I quickly acquired his chest below his neck and squeezed off. A solid “dup” confirmed my sight picture at the instant of firing and the ram flashed off to our left. This time we found bright blood where the animal was standing, and more on the yellow grass leading off in the direction he had run. Without much difficulty, we followed after a short wait. He lay about fifty yards further on, his white belly bright in the morning sun. I felt a weight lifted from my shoulders and wide grins spread across our faces. The bullet had centered his breast bone and there was no apparent exit wound. But there was no shoulder wound either! The realization that I had shot a different ram hit me with a thud.

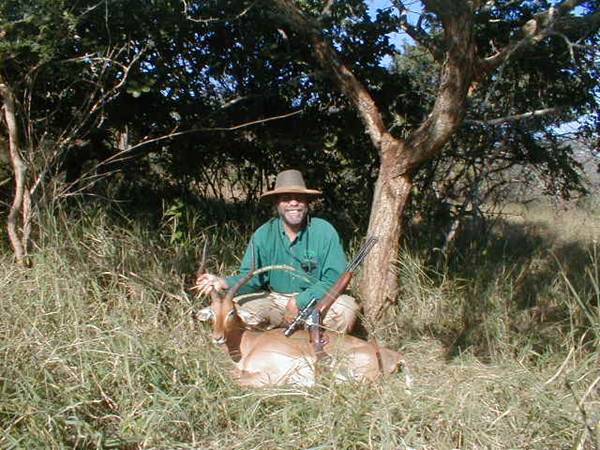

|

|

|

A Case of Mistaken

Identity: Impala Ram was in the |

While the Impala was being dressed out, I resumed my

waterhole vigil. Around

The pursuit of the wounded ram continued that afternoon with an initial drive through the area. Since game is not shot from or near vehicles on this property, they are not alarmed by a vehicle so this a good way to search for game. But the early season thick bush made this a hit-and-miss tactic, so we resumed the hunt on foot. While glassing a somewhat open area, we noticed a large group of Warthog moving in single file angling slightly away from us across our front, from left to right. I made a quick decision that taking a shot, if one presented itself, would enable us to check that box while not hindering the search for the Impala. Kneeling again, but this time resting the foreend on my guide’s shoulder for extra support, I watched the warthog cross through the treed but almost grassless glade. It was hard to distinguish the male from the larger females, but with uncanny ability, my guide whispered “female” each time I asked “this one?”, until at last a visibly larger hog bringing up the rear stood momentarily in my crosshairs. “That one!”. The words had barely been said when the rifle barked and the hogs went into high gear. There was no thud this time, but I was sure of the shot. The crosshairs were solidly on the shoulder at the critical instant. The sound of running hogs and cracking twigs was soon punctuated by a large crash, and then silence.

|

|

|

Mature

Warthog Fell to a Single Bullet in Quartering Shot. |

No tracking was necessary. The hog lay, facing the wrong way, about thirty yards from the place where he was hit. The bullet had taken him behind the diaphragm on his right side, and exited forward on his left shoulder. From this, I concluded that he had been angling away to a much larger degree than he appeared to be in the scope.

With considerable effort and renewed confidence, we dragged “Mafuta” (Zulu for fat one) by his large curved tusks to the road and loaded him into the vehicle. The Impala hunt resumed.

From our vantage point near the vehicle, a herd of Impala were visible high on a ridge to our front, about four hundred yards off. We could make out a large ram with them, but he appeared to be moving normally. I continued observing him through my 8x32’s. As he moved behind some brush, I thought I saw a hint of a limp. Or was it just the terrain? We lost no time moving into position for a closer look as the sun was getting low behind us. We located the herd near the crest of the hill, but they had us pinned down on the slope below them. Catching only glimpses of their heads and ears in some taller grass, we decided to wait as the impala were moving across our front. The shadows lengthened, signaling a halt to the hunting. But in pursuit of a wounded quarry, the normal rule doesn’t apply. Thirty minutes before dark, we heard the ram’s guttural call (the rut had begun, during which time dominant Impala rams make a harsh sawing grunt to intimidate potential rivals) but off the left. Moving closer, we spotted him and were in turn spotted. Still unsure, I watched the nervous animal through my scope from a kneeling position as he moved, first to the right, and then to the left and away, moving toward the crest of the hill. With a jolt I saw unmistakably that he was limping slightly and had stopped just short of disappearing over the ridge, angling away from me and to the left. I quickly fired at his left shoulder, the distance being around 150 yards. I called the shot as a little low, possibly too low as evidenced by the sound of the bullet hitting a rock and whining off toward the ocean. Nevertheless, we made a quick search of the area and finding nothing, marked the spot by breaking a tree limb.

That night, I woke several times, listening to the sounds of

the African night. A Bushbuck or Nyala barked loudly,

five or six times, in the dense brush alongside the river. Every now and then,

a Bush Baby would cry out from the limbs of some tree, sounding remarkably like

a dying rabbit varmint call. “Whaa, whaa , whaa, wha, wha.”

I made a mental note that using that particular sequence of sounds to call

varmints in

The harsh call of the Natal Francolin wakened me at first

light. I gathered up my gear and grabbed a quick breakfast, before heading back

to the scene of the second shot. After a thorough search of the area, finding

nothing but a metallic streak on a large flat rock, we reluctantly turned our

attention to Nyala and Bushbuck in the lowlands along

the river. But first, I inspected the carcasses of the Impala and Warthog, now

hanging in the walk-in cooler. Contrary to our first impression, the 235 grain

Speer bullet traveling at just under 2300 fps had penetrated the full length of

the “accidental” ram, exiting through the haunch after traveling through four

feet of flesh and organs. We had been unable to detect the exit hole because it was essentially the same size as

the entry wound, and furthermore there was no bleeding at all from the

hindquarter. The blood from the entry wound emanated from the heart, which was

squarely punctured by the bullet. There was almost no meat damage surrounding

either wound. The warthog told the same story, minimal meat damage, although

the animal had bled noticeably through the exit wound where we found him. It

dawned on me that the Speer bullet was not expanding at all, but acting just

like a military-style solid! This began to explain why the first Impala was

still running around with little evidence of being hit, when by all rights he

should have expired. The bullet must have passed between the shoulder blade and

the ribcage, a natural cleavage plane, and exited without damage to organs or

bone.

It is impossible to move through the almost impenetrable brush that parallels

the river bed at all, let alone silently. Every bush seemed to have thorns of

some description, ranging from the intimidating straight white thorns of the

Sweet Thorn, to the vicious curved hooks of the Buffalo Thorn. The Umbrella

Thorn has some of each, for good measure. The only feasible method of hunting

is thus to still hunt along the track, or in the river bed itself.

Not far into along the trail, which winds alongside the river under a canopy of yellow Fever Trees and Wild Figs, we spotted movement to our left. A young male Nyala was browsing not twenty yards from us. His coat was still red, so we quietly moved on all the while checking for more sizeable companions. Spotting a piece of bush moving off to our left, we stood silently waiting for the browsing animal to show himself. Glassing through the brush, I observed a very thick pair of spiral horns, gleaming black with dew, moving as the animal fed. My first thought was that they belonged to a Kudu bull. But the shape suggested Nyala. Suddenly, the animal bolted down toward the river with a crash, as I noticed that the wind had shifted. My guide’s eyes were as big as mine, as he whispered “Very big Nyala bull”.

The rest of our hunt yielded only rustles in the brush, and

a sighting of a pair of Red Duiker. A specialized and quite expensive trophy,

these were not on my list. Mark described them as being quite popular with

hunters who were working on the smaller species, and in the same class as

Klipspringer. Their distribution is limited to pockets up the East Coast of

Africa through

As on most days, hunting stopped around

The Nyala hunt resumed after siesta, this time in pursuit of a pair of bulls spotted moving up one of the ridges away from the river, mingling with Impala. This made the stalking very tricky, as the Impala acted as sentries. After being spotted twice, and having a large bull move off just as I was applying tension to the trigger, we were able to move into position some 75 yards from the Nyala half way up the back side of a ridge. One of the bulls lagged behind as I moved into a firing lane again in the kneeling position. He was quartering away, facing to the right. At the shot, which was good if a little left of the optimal placement, everything exploded and we went immediately to look for tracks and blood. Finding none, we followed in the general direction and soon heard an animal clattering away through the brush. This was our bull, he had lain down within 50 yards as evidenced by a small amount of blood in a bed under a shady tree. Following up, we found a second bed some distance down toward the river, and then heard movement in the thick brush off to our right. Approaching this area, we spotted a group of monkeys and attributed the noise to them. However, after quite an extensive search of the area, we again searched in the vicinity of the noise and found the Nyala dead right where we last heard him. In all, he had moved about 750 yards from the shot, rather more than I would have liked, and left very little by way of a blood trail. Upon inspection, this was explained by the bullet entry in the lower right flank, and exit behind the left shoulder. The two holes were caliber-size, and the shot was 6 inches further back than it should have been, missing the vital organs entirely (as later evident when the Nyala was dressed out). There was only a very little blood seeping from the exit wound.

This particular bull measured 27 1/8”, above average for the property and respectable by any standard. The record is around 32”, with Rowland Ward minimum being 27”. In truth, I could not see the horns when I fired, preferring to take a modest trophy than passing up what could have been my one and only opportunity to take such a rare and elusive quarry. I have made the other decision while hunting Kudu, for example, only to come away empty-handed at the end of a long week of hunting.

|

|

|

Author’s 27” Nyala. Larger Bulls were Spotted, Before and After. |

A picture was now emerging regarding the effectiveness of this particular

bullet/caliber combination. The bullets had outstanding penetration, but would

not expand if only flesh or organs were hit. In the latter event, animals went

down within earshot. Both instances where animals did not expire quickly were

clearly the fault of the shooter, not the hardware. One school of thought is

that this performance is exactly what is called for, namely one shot kills when

shots are placed correctly with hardly any meat damage; and minimal damage when

a flesh wound occurs, giving the animal a reasonably good chance of survival.

The other school of thought is that one wants a more destructive bullet, as a

marginal hit, in addition to generating a much more visible blood trail, is

likely to prove fatal as pieces of bullet metal penetrate a wider cone

increasing the chances of a fatal wound.

Campfire discussion led to the conclusion that the jury was still out, and more evidence should be collected.

In that vein, hunting continued for the last remaining days of the Safari. The early poor shot on the first Impala and the efforts to locate the wounded ram had consumed a large portion of the hunt, leaving limited time to pursue the remaining species. Bushbuck being the main omission to date, we returned to the river in search of one early the next morning.

The morning’s hunt was conducted in the river bed itself. A winding channel, not more than thirty feet wide, twisted and turned between high banks covered in thick brush. The river bottom was sandy in places and covered in rather noisy pebbles and rocks in others. I took the lead as any shots would have to be made very quickly.

We still-hunted the upper portion of the river first, as the breeze, if any,

was moving downstream. Progress was agonizingly slow, as any still-hunt should

be. The strangeness of it was that we were totally exposed, relying on grassy

sandbanks and turns in the river to allow us to approach unseen. Unlikely as it

seemed, we found to our amazement that the technique worked! Our first

encounter was with some moving grass and reeds on the right bank. Something had

obviously entered the river bed not 20 yards ahead. We moved cautiously

forward, finding ourselves face-to-face with a Red Duiker who looked at us,

looked away, looked at us again, and then gave a little whistle and was gone.

Fifty yards upriver, we spotted a Nyala bull while

peering round a bend. The single bull turned out to be a group of three mulling

around a muddy spot that was still somewhat wet. One of the group was over 27”,

one around 27” and one smaller with a malformed horn. After observing them

quietly for a minute or so, they started moving in our direction, sending us

scurrying back around the bend in into the brush in an effort to surprise the

trio with a photograph. However, they left the river bed diagonally before

reaching us.

The breeze was against us at this point, so we looped around downwind using the

parallel road and reentered the river bed about a kilometer further downstream.

Agonizingly, we picked our way across the pebbled sections, spotting Red Duiker

and a female Nyala. Not twenty yards further, we saw

a whitish mane sticking up above a grassy bank that turned out to be a

respectable bull and another female. We showed ourselves, causing them to take

flight into the bush. Thinking we had now exhausted that particular stretch, we

were about to move on when we heard a loud bark, very close to our position.

Thinking this to be a Bushbuck, we very slowly worked our way around the bend

on a sandy bank covered in high grass on the inside of the corner. There, to

our amazement, stood another bull cropping the sweet shoots and grasses in the

river bed. But this was no ordinary bull, it was the

monster we had seen previously. His horns were as thick as those of a kudu, and

his body almost as large but darker. He sixth sense or his nose must have set

his alarm bells off for after a minute or two trickled by, he suddenly lifted

his head and jumped up an almost vertical bank of red soil, to stand broadside

at the top of the bank for twenty seconds, before moving off into the bush. In that twenty seconds, I decided to shoot and then not to shoot

three times. In the end, concern for my checkbook overwhelmed my ardor

and I let him go. This beautiful trophy was no more than twenty yards from us,

broadside, with nothing but air between us. My experienced guide estimated his

horn length to be at least 30” after he had disappeared.

We saw this bull a third time, crossing the road ahead of us as we sought the elusive Bushbuck on the last morning. Again, I could have taken him as his head was stuck in a green bush while his body protruded into the roadway. But by this time, I had resigned myself to leaving him for another lucky hunter so we just watched him feed off into the brush.

Thus ended the hunt, with a question mark

hanging over our project. Would this rifle perform on yet larger

antelope such as Kudu? There was only one way to find out, and

In the next article in

this series, the author tests the 375/444 double on Warthog, Hartebeest, and

Kudu in the thornveld of

Russ Gould is owner

and operator of Double Gun Headquarters (Doublegunhq.com), a multiseller virtual gunshow

specializing in fine double rifles and shotguns. He also offers African Safaris

with personally selected operators to

Copyright R. Gould 2014. All Rights Reserved